Intelligence doesn't exist. Let's talk aptitude instead.

We need to move past human-centric definitions of intelligence.

There’s no such thing as intelligence. Nobody can decide what it means. It’s this weird mishmash of concepts that actually mean more like ‘what makes us humans special’, and facing the final bout of specialness leaving, we’re scrambling to redefine it. Just like the first step in understanding astronomy more broadly was dropping the Earth-as-the-center-of-the-universe reference frame, I think we need to drop the humans-as-the-definition-of-intelligent reference frame.

I’m going to explain why intelligence is a counterproductive term, why we’re evolutionarily wired to be bad at reasoning about it, and why I think a much better term is aptitude at certain tasks.

We can’t decide what Intelligence is

I grew up playing chess on computers, so it was always obvious that they were much better than us at the game. It was pretty surprising, then, to learn that there was a point where it was considered the summit of intelligence. Some researchers even thought solving chess was the key to solving AI. And today, I can scale up the minimax algorithm from my intro to AI class and beat most people.

This highlights the bigger issue- our definitions of intelligence keep changing as AI advances. Chess is just one of many examples, but I’ve seen this firsthand. In 9th grade, I tried to make an app that created revision questions from a photo of a textbook. I had to use horribly complex classical NLP tools and make syntax trees and use heuristics and the output was still terrible. Today, LLMs can do it out of the box. And we still think ‘nO, tHiS iS juST neXt TOkEn PrEDiCtIon’

Because we don’t have a clearly fixed line in the sand that says ‘this is what intelligence is,’ we give ourselves the opportunity to redraw it the moment something crosses it. It’s almost like it means ‘things only humans can do,’ and we reserve the right to change what it means the moment ‘things only humans can do’ shrinks. And the more I thought about this super human-centric definition, the more it reminded me about how we talked about the soul. Stick with me here for a bit.

Definitions of intelligence are metaphysical and overly anthropocentric (just like the soul)

Here’s what we thought about the soul.

It was obviously something humans had, and inanimate objects didn’t.

Whether animals had one or not was up to debate.

But then we started thinking- what exactly is this soul thing. And where do we find it? We went so far as measuring people’s bodies as they died to see if this soul thing was leaving the body. So far, no convincing evidence has been found.

Some people might say that the soul is a more intangible thing, but if it’s so intangible that it can’t affect the physical world and physical measurements, then it doesn’t really matter if it’s real or not, it can’t affect us as physical creatures.

Okay let’s think about intelligence.

It’s something humans obviously have, and inanimate objects don’t.

Whether animals have it, and the extent to which they have it, is up to debate.

But now we’re thinking, what exactly is this intelligence thing, and all our metrics are failing.

Some people say it’s a more intangible thing, like a fuzzy mix of problem solving/agency/ goal directed behavior, but if it’s so fuzzy, then maybe it’s not a great definition?

So our definitions of intelligence are as kooky as the definitions of the soul that seemed to speak to intangible metaphysical ‘human-essence-y’ qualities.

It’s hard to reason about intelligence because of how we evolved

Living things need to solve various problems in their environment to continue propagating. Humans, for example, need to regulate body temperature, extract energy from food, move, think, socialize, and do long term reasoning, amongst many other things. But we don’t find regulating body temperature or movement impressive because basically every single living thing can do these things. But reasoning, planning and language are unique to humans.

Humans, the extremely social creatures we are, anthropomorphise just about everything, to the point that we can anthropomorphise inanimate objects, and see faces where they are none. It’s like we have a ‘human-finding’ drive. And if reasoning, planning and language are unique to us, while evolving, the only things we’d encounter that could do them well would have been other humans.

This has important implications on how we think:

If (can reason/plan/speak) therefore (intelligent) then (human): In our ancestral environment, being human meant being able to reason, plan, and speak, and being able to reason, plan, and speak meant you were human. The latter half of that relationship doesn’t hold anymore. LLMs can reason and plan and wield language, but they aren’t human. But because we’re evolutionarily wired to not understand that, it can be easy to assume human-ness where there is none.

If (not human) then (not reason/plan/speak) therefore (not intelligent): We systematically devalue the intelligence of other creatures. Just because they are not human, we assume they cannot reason, plan, or use sophisticated language. But we have more and more evidence that animals do have sophisticated abilities that we completely overlook. Bees share information in a sort of language. Chimps can likely long-term plan.

Intelligence seems like it exists in many forms, and not all of them are tied to human-ness, but because our definitions of it are so tied to human-ness, we still find it hard to talk about.

I mean, the Turing Test, which was the generally accepted test for human intelligence, is so human-centric literally about whether a system can seem human enough to fool a human talking to it. It’s clearly showing how primitive it is as a test because LLMs can definitely beat it now, but they’re still clearly missing things to call them fully ‘intelligent’.

Intelligence is a bad abstraction

The Turing test breaking down is just a symptom of how bad of an abstraction ‘intelligence’ is. Consider this:

Individual ants aren’t intelligent, and yet as a swarm, ant colonies can find food, communicate, and build things much bigger than themselves. Is the ant colony, then, the thing that’s intelligent?

Cells display goal directed behavior at their own scale, but put a few trillion of them together and they’re a human who displays completely different goal selection and emergent behavior.

But why can’t a few billion of us humans display completely different goals and intelligence, the same way an ant colony does?

The phrase we’d use here is that they’re all ‘displaying some form of intelligence’, but what does that even mean. What form of intelligence?

A pond can ‘maintain’ its internal temperature without ‘thinking.’ A slime mold can navigate a maze with no brain. Are we to say that these things aren’t intelligent? But it feels odd to say so, right? Because it feels like they aren’t ‘alive’, and so how could they be intelligent? They’re just systems.

So can something that’s not alive be intelligent? Not in the way we currently think of intelligence. This is what I mean when I say it has some vague notion of ‘essence bundled with it’, it feels weird to call something that isn’t alive, like a pond, ‘intelligent’. In a way, intelligence is also bundled with ‘aliveness’.

And so if something displays intelligent behavior, should we treat it like it's alive? But what is aliveness, now? Talking about it the way we do raises more questions than it solves.

Aptitude is a more objective measure of the abilities of systems

So intelligence as a term sucks.

We can’t decide what it really means

The definitions have deep metaphysical undertones

They are so tied to whether we think something is alive or not.

So what’s a better thing to talk about? I’d say, abandon all vague, human essency associations we get with the word intelligence, and instead use ‘aptitude’. Aptitude, as I’m defining it, is saying here’s a task, here’s how we’re structuring it, here’s how we define success in this task, and now- how does the agent perform based on our definitions of success. In thinking about aptitude, we need to pay extra attention to how we’re actually structuring the test, and the implications on how we’re defining success.

Aptitude, here:

Has a clear definition: because we’re clearly stating that it’s a measure of specific ‘ability’ at certain tasks, it doesn’t have a all encompassing definition the way intelligence does. And so we can scope it to specific problems and actually talk about the same thing when discussing

Doesn’t have deep metaphysical undertones: We can judge how well ponds maintain internal temperature without considering whether they’re ‘alive’. There’s no assumptions of agency or embodiment or consciousness.

Doesn’t specifically refer to humanness: A software system can have an aptitude at something, so can a company, or a city, or a program, or a cell.

What we call ‘intelligence’ is actually just systems that have high aptitudes at things that humans have high aptitudes in (see the section on why it’s hard to reason about intelligence because of how we evolved above).

I’m convinced that having a less human centric view of intelligence will make talking about these systems much more productive. The important point here is also that the test design and definitions of success in the task are extremely important, and something that just thinking about blanket intelligence can miss.

Some examples of how human-centric definitions of intelligence cause trouble

Non-human models of the world

When Gibbons were tested by placing a banana outside their cage and a stick in their reach to grab it, they didn’t do very well. “Chimpanzees will do so without hesitation, as will many manipulative monkeys. But not gibbons.” But then scientists realised that they weren’t testing the Gibbons properly. Gibbons are exclusively arboreal creatures. They basically never need to pick things up from the ground. And so, when they did tool based tasks with the tools at eye level, the Gibbons did as well as other apes. “Their earlier poor performance had had more to do with the way they were tested than with their mental powers.

Or consider LLMs, which couldn’t perform very well on mathematical tests, but the moment we tell them to think step-by-step, they suddenly work much better. It’s because we’re testing them on their own model of intelligence, not ours. They clearly have mathematical aptitude, but we’d have stopped short had we not probed it, just because it doesn’t adhere to our model of intelligence.

Obedience and perceived intelligence

“Are we smart enough to know how smart animals are” has this anecdote where Afghan hound owners get offended that the breed was ranked last in terms of intelligence. They lament about how this is because they’re independent minded and don’t follow orders, making the list more about obedience than intelligence.

I wonder if we’re doing this with LLMs. RLHF’d models are way more obedient than out of the box LLMs. But are we sacrificing some element of creativity here? Are we even trying to make a general intelligence that is self-directed, or are we trying to explicitly make intelligence without self-directed behaviour, so we can just enslave it? We might be calling RLHF’d models more intelligent just because they’re better at fitting our model of ‘obedient assistant’.

Motivation and perceived intelligence

Another example from ‘Are we smart enough to understand how smart animals are’- They tested chimps and monkeys on tasks where they differentiate between objects based on touch. The monkeys kept at it and gave good data, but the chimps immediately got bored and tried to play with the researcher instead. It’s not that they were dumber, they just weren’t engaged enough to try. With chimps, it’s obvious they’re smarter than monkeys. But what if it was an entity that we didn’t have accurate mental models of- how would we know they had high aptitude at things without just probing it?

It also shows that intelligence doesn’t imply success in a task without also taking into account other factors like motivation. In this case, the monkeys definitely had a high enough aptitude in the task, they just didn’t care enough to show it. Makes me think of school classrooms- at a school I’m volunteering at, the students who finish tasks earlier get reprimanded more, because they inevitably sit around and get bored and go on their phones.

What does this explain?

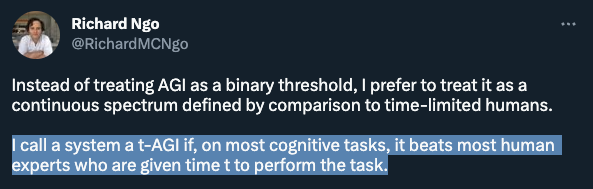

Here’s some things I’ve seen on Twitter that I think this framework helps extend/explain

‘If they can perform it at all’ -> whether the system has an aptitude in that task

‘On most cognitive tasks’ -> aptitudes in different domains

The LLMs don’t have high aptitudes at having world models for agent management (yet), but it would be easy to assume that they do because they have aptitudes at other human-like things.

This is still the best model of LLMs behaviour I’ve read so far, and is a complete departure from thinking of them as human like intelligence.

Conclusion

Stafford Beer argued that brains and much of intelligence are ‘exceedingly complex systems’, ‘systems that are so complex that we can never fully grasp them representationally and that change in time, so that present knowledge is anyway no guarantee of future behavior. ” The only way to test these is by prodding them in many different ways, so we get many different angles of the aptitudes of the system- an idea that ties well with Wolfram’s computational irreducability.

There is a much larger variety of systems that have aptitude than we could have imagined. Just like how we moved past human-centric definitions of soul, we need to move past human centric definitions of intelligence.