What causes online outrage?

The lunch hall effect: what high school has to do with twitter mobs

A while back, my Twitter blew up with people getting offended at a man named Tom Nichols, who’d quote tweeted a controversial opinion. Well, seemingly too controversial:

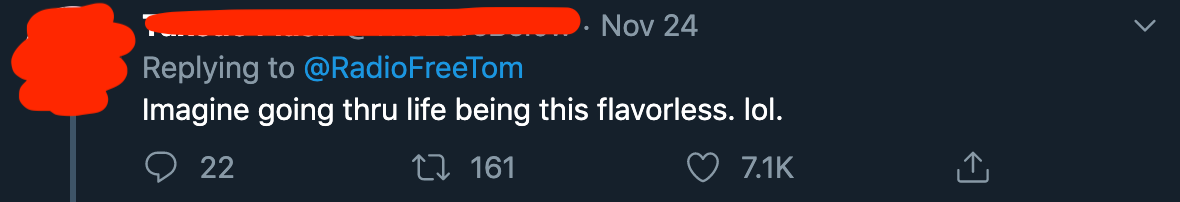

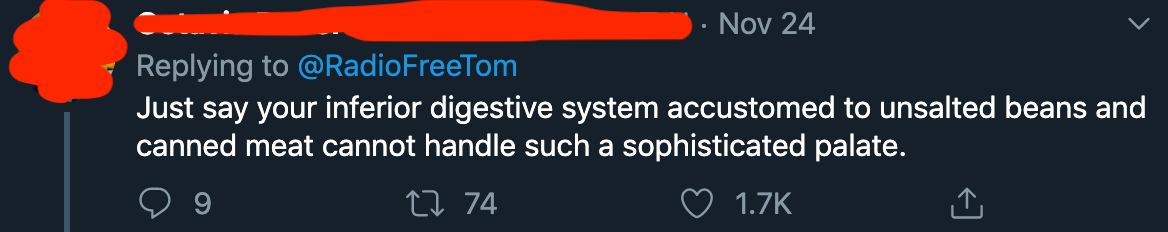

Look, as an Indian myself, I get it. It’s one thing to say Indian food is terrible, it’s another to say ‘we’ pretend it isn’t. But the responses to his tweet seemed slightly overdone:

I get that his tweet was quite culturally insensitive, but I don’t think an opinion about food deserves even close to such an outcry. This is people calling him a racist because he doesn’t like a cuisine.

But this isn’t specific to this example. From J.K Rowling to Kevin Hart, It seems like ‘outrage’ is becoming an extremely common occurrence on the internet. I wrote this to make it clearer to myself why it happens, and how to avoid jumping on the outrage bandwagon myself.

I’m lucky enough to go to an international school with students from several different countries and backgrounds. On a given lunch table, I expected that there’d be a mix of many cultures. In my mind, each table should have had the same average diversity as the entire school

But I realized this isn’t the case at all. Apart from some variations, most groups are filled with similar people. Asians group with Asians, Indians group with Indians, Eurasians group with Eurasians. This doesn’t mean that anyone actively avoids other groups or students from other cultures. Just that generally, students spend time with people who look like them.

And for a while, I was confused as to why this was happening. School as a whole is mixed evenly. Classes are mixed evenly. Why was it that when given a choice, students don’t group evenly? But I think I got an idea of why. I call it the lunch hall effect:

Humans tend to group together with people they agree with, and agree with people they’re grouped with.

You naturally tend to avoid people whose opinions or values don’t match yours. If someone constantly disagrees with you, or constantly talks about their amazing-new-house-plant-that-you-totally-definitely-care-about, you tend to stay away. This behaviour applies online too. If you follow someone and they tweet too many things you dislike or find irrelevant, you unfollow them.

This means that you slowly iterate into groups who share the same opinions and values that you do.

But independent of who you choose to align with, your views are shaped by the people around you. The more you hear about something, the more you agree with it. Let’s say you’re a farm boy that gets involuntarily involved in a rebellion against a brutal dictatorship. Chances are you’ll agree that the Death Star should be blown up.

But what if you somehow entered the story from the Empire’s side? Perhaps you’d be convinced to destroy the small group of terrorists who were threatening the stability of the galaxy. This is an important feature of the groups you enter. If you aren’t careful, you’ll begin to understand the world from a very narrow perspective and be convinced you’re right.

There’s an easy heuristic to test for this. How many opinions of the people you spend time with, online or not, would you say you strongly disagree with? The chances that your community has everything right is very small. If you find it difficult to answer this question, that means you’re probably letting your group think for you, instead of thinking critically for yourself. This is, as you’d have guessed, called groupthink/being in a bubble.

When you’ve been exposed to the way a certain group thinks for long enough, it becomes a part of your identity. So when you see any view that opposes it, you can’t even consider it. You merely become angry and think the other side is an idiot.

In a school lunchroom, all voices are not created equal. Some people don’t talk at all, some are just generally quiet, and others speak normally within their own groups. But most of the noise in the hall comes from a disproportionately small number of really loud people. It’s similar online. Most people speak only within their small communities. It’s a very small percentage that causes most of the chatter.

But online, being loud doesn’t get you seen. Being shareable does. And it’s the extreme voices and opinions that get shared the most. Between a tweet of someone with a scathing take and a mild, reasonable one, you’ll be more inclined to share the former. The ability to provoke a reaction is the evolutionary currency on which internet content survives.

The takes that represent the moderate viewpoints probably won’t have enough escape velocity to exit another bubble and enter yours. Only the extreme takes will have the energy to do so. Information that’s engineered to be shareable tends to lack substance or can be blatantly false. Because of this, the few glimpses into the world outside your intellectual bubble won’t really be representative of reality.

The amount people get outraged online can be summarised with a simple formula.

Amount of outrage = Frequency of outrage-worthy content encountered * probability of outrage

Unlike online, in real life, there’s no mechanism to constantly come across extreme takes from outside our filter bubble. People generally share their opinions within their own small groups. Because of this, the frequency of outrage-worthy content encountered is low. But since it’s the extreme takes that get shared online, and these takes can come from anyone with access to the internet, it's much easier to come across someone you disagree with online.

The real-world equivalent of calling someone out for something they wrote online is like reading something you disagree with in a newspaper, getting really angry about it, searching for the writer’s address, driving over to their house, ringing their doorbell, and telling them they're an idiot. And then driving all the way back home. The activation energy required to vehemently disagree with someone online is just a few keystrokes.

Because of this, you come across outrage-worthy content online more frequently, and you’re more likely to react to it.

Since it’s easier to call people out online, and you’ll come across content that’s easier to call out, there’s a very high chance that someone in your bubble will have a reaction to something extreme if they come across it.

Everyone in the bubble gets to see someone get outraged at a clearly idiotic (to them) take. They are now more inclined to react themselves, which spreads the content even more. This effect is particularly true for accounts with many followers. Once an account with many followers calls someone out, it is almost as if an authority figure has officially stated that the person being called out is definitely wrong.

And once you’ve seen enough people jumping on the bandwagon, sitting it out seems odd. So chances are that you will join them as well. Your followers see you jumping on the bandwagon, so they do too. This eventually snowballs into the #cancel<insert person here> outrage mobs we see online.

This entire process only reinforces the bubble. People who find constant extreme takes exhausting will leave. Those who make these extreme takes will further reinforce the group’s identity. Because their worldview will be much narrower, outside opinions will seem more extreme. Which will cause them to get outraged more.

Always someone to get outraged about. Always someone to cancel. We’ve found ourselves a self perpetuating cycle of internet outrage.

Part 2: Why is internet outrage bad? and Part 3: How do we stop internet outrage? are on their way.